Tips for Improving Your Toddler’s Speech Clarity

It can take up to about second grade for a child to acquire fluent speech that is free of articulation errors. However, certain patterns of errors can make a child less understandable to his or her communication partners. This also applies to younger children. Today I wanted to highlight some of these patterns and give you, the parent, some suggestions for improving toddler speech clarity.

Leaving off the last sound of a word

This is quite common in younger children, which is why we expect that not everything an eighteen-month old can say should be understood. As you can imagine, leaving off the last consonant in a word can make it quite difficult to understand the word the child intends to use. For example, “bae” could mean “bath” or “bad” or “bag”. The only way we know which one the child is referring to is the context clues. In fact, a few years ago, I recall working with a boy whose speech was quite unintelligible. He had many things we needed to work on, but this pattern of leaving off the last sound of a word was my single highest priority for him. By age two, kids should be able to put consonants onto the ends of words, with few exceptions. To encourage kids to do this, I have found that working with words that end in the /m/, /p/, /t/ or /k/ sounds is very helpful. Use words like: game, mom (not mama), up, cup, hat, car, sock, duck. Exaggerate or accentuate these consonants when you say them and model for your child that you also want him or her to make the same exaggerations.

Errors on consonants at the beginning of words

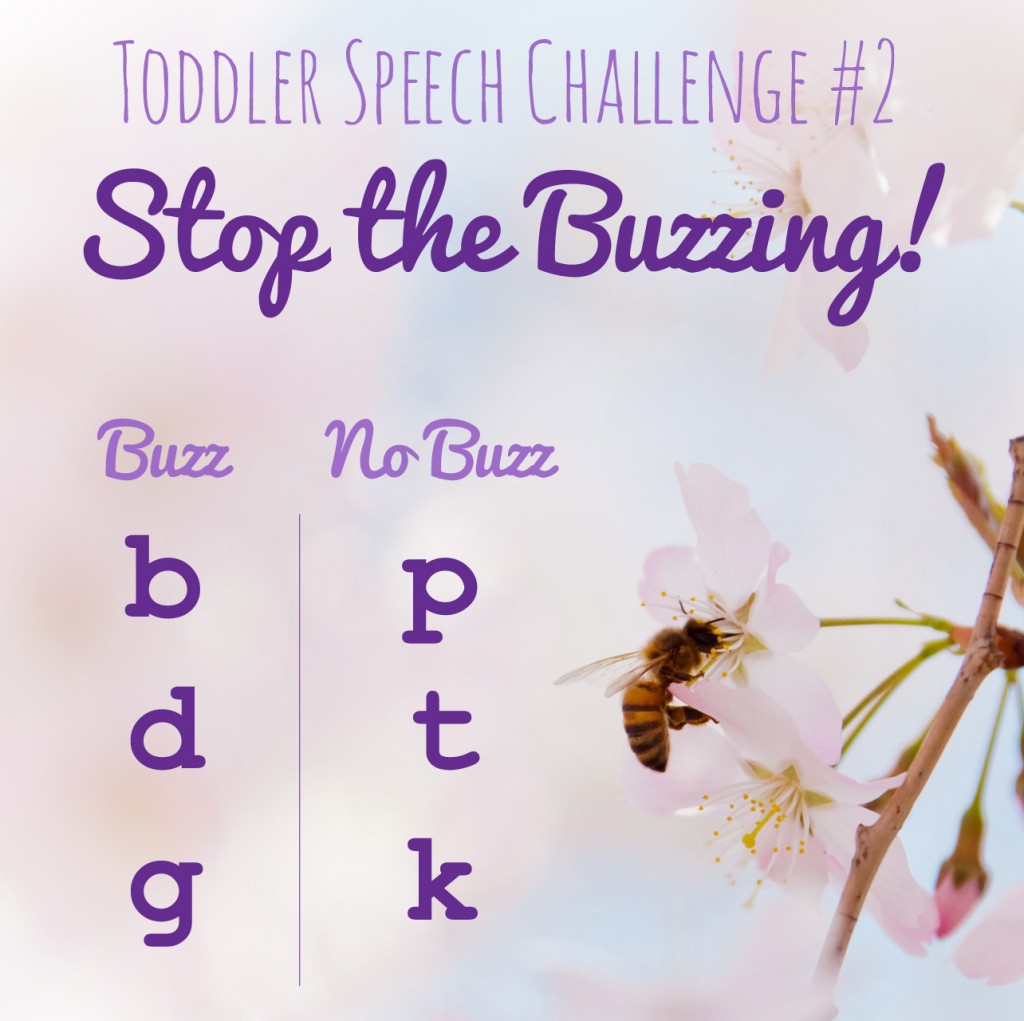

Another common error pattern in young children is something called initial voicing. Examples of this are when a child says dape for tape, big instead of pig, or gat instead of cat. Take a quick moment to think about what your mouth is doing when you say /p/ vs. /b/, /t/ vs. /d/ and /k/ vs. /g/, you may notice that your mouth is actually doing the same exact thing for both sounds! The only difference lies in the throat. For /b/, /d/ and /g/, but not for /p/, /t/ and/k/, your vocal cords are vibrating. If you put your finger on your throat you can feel this vocal cord vibration as a buzzing sensation. Vowels are also sounds that produce this buzzing.

What children have trouble with here is going from a non-buzzing sound to a buzzing sound; they prefer to keep it all buzzing.

One way to get your child to say either of these sounds correctly is to whisper. When you whisper, you don’t buzz your vocal cords. So have your child whisper a handful of words that begin with any of these sounds that he or she cannot currently say. This has the effect of showing your child that he or she can indeed make the sound. The next challenge is to put this skill into actual words.

In English, these /p/, /t/ and /k/ sounds have a nice, strong burst of air when they’re said at the beginning of a word. So in order to get kids to have that initial learning breakthrough, we want to emphasize this burst of air. I like to use external cues to really show kids what to do. For example, I like to use a single piece of tissue paper and hold it about three inches in front of his or her face. Now have your child say pig (or tub or cup). If he or she says the /p/, /t/ or /k/ sound correctly, the tissue paper will get flipped up. If he or she says a /b/, /d/ or /g/ sound (in other words, say it incorrectly), then the tissue paper will stay where it is. This little trick can be very helpful toward improving your child’s overall speech intelligibility. This sound pattern, of turning an intended /p/, /t/, or /k/ into /b/, /d/, /g/ respectively can significantly affect how well understood your child is. It is a good idea to tackle this as soon as possible.

In English, these /p/, /t/ and /k/ sounds have a nice, strong burst of air when they’re said at the beginning of a word. So in order to get kids to have that initial learning breakthrough, we want to emphasize this burst of air. I like to use external cues to really show kids what to do. For example, I like to use a single piece of tissue paper and hold it about three inches in front of his or her face. Now have your child say pig (or tub or cup). If he or she says the /p/, /t/ or /k/ sound correctly, the tissue paper will get flipped up. If he or she says a /b/, /d/ or /g/ sound (in other words, say it incorrectly), then the tissue paper will stay where it is. This little trick can be very helpful toward improving your child’s overall speech intelligibility. This sound pattern, of turning an intended /p/, /t/, or /k/ into /b/, /d/, /g/ respectively can significantly affect how well understood your child is. It is a good idea to tackle this as soon as possible.

Stopping Air Flow When It Shouldn’t Be Stopped

Another sound pattern that is a serious culprit in reducing your child’s speech clarity is something called, actually pretty intuitively, stopping. Some sounds necessarily and momentarily stop air flow in order to make the sound correctly. Right now, try saying the word “eating”. You’ll notice that when you say that first vowel (or “ee” sound) that in order to say the /t/ sound, you have to place your tongue where the upper front teeth and gums meet and stop the flow of air. That’s because this /t/ sound requires that you stop the air flow. Now try to say “easing”. You’ll notice here that the air never stops flowing for the entire word. Many kids will stop the air flow where the air should actually keep flowing. This again can really affect a child’s speech intelligibility and should be addressed as soon as possible.

Any sound that requires continuous air flow can become subject to this stopping that younger kids can do. Common examples of these sounds include: /f, v, s, z, th, sh/. So you might hear your child say he’s not four years old, but “tor” or “door”. I like to use something called minimal pairs, in speech therapist parlance. This is where you have two words that only differ in one sound, the sound you want him or her to say correctly and another sound. Let’s assume your child cannot say the /f/ sound. Good minimal pairs could be fin-tin, fake-take, Jeff-jet. You can mix up where in the word the target sound falls. This can really allow you child to perceive the difference between what they’re saying and what they should say to do it correctly.

These Patterns Should Phase Out by 2½ Years Old

These three speaking patterns can be very common in toddlers. And although they can be considered developmentally normal in a two year old, as a child moves toward two and a half, if these patterns are still present, it can mean that your child’s speech may be in need of attention from a great local speech pathologist. However, the above tricks can be excellent places to start. In some cases, a child may just need you the parent to call attention to these patterns and that’s enough to get him or her going on the path to correcting it. But when in doubt, always consult a qualified speech pathologist.