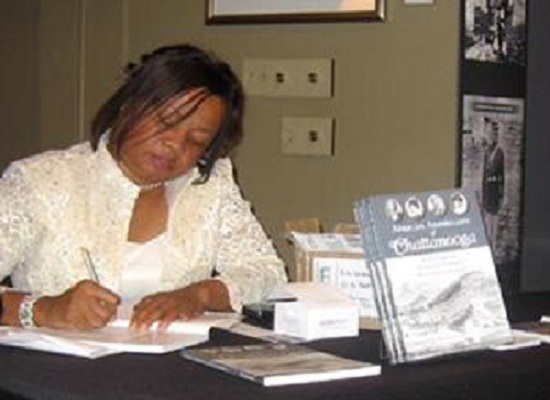

An Interview with Rita Lorraine Hubbard – Special Needs Teacher

This week we’re speaking with Rita Lorraine Hubbard, a former special education teacher with over 20 years of experience working with special needs children. Rita is also a children’s book author and founder of the children’s book review website, Picture Book Depot. Check out Rita’s writing at “Rita Writes History.” As if that weren’t enough to keep her busy, Rita Lorraine Hubbard also specializes in teaching sign language to new moms and babies. She stresses the importance of encouraging communication at an early age to facilitate academic progress, as well as social and emotional development. Today, Rita has shared a glimpse into the world of special ed classrooms. She discusses the importance of parental involvement in the classroom, as well as a typical day for a special ed student.

As a former special education teacher, you also served as a liaison to parents. Can you talk a bit about the role of parental collaboration in ensuring the child’s academic success?

Parental collaboration was important on two major scales. First, it showed students that their parents were as serious about their education as we the teachers were. It demonstrated how the two environments – home and school – were more intertwined that students could even imagine, and that if the school knew what was going on at home and the parents knew what was going on at school, success in the classroom was almost guaranteed to happen.

But parent collaboration was important in another way that many schools don’t like to talk about. There was (and probably still is) nothing worse than an MIA, a missing-in-action parent. (By the way, this is my term and no one else’s.) Whether they intended to or not, MIA parents showed our school that absolutely everything in the world was more important than their own children, and they showed this by never showing up for anything: no PTA meetings, no Open House, no MTeam meetings…nothing.

This often led to hard feelings from teachers who desperately needed the parents in order to control the children and/or to obtain the supplies and support they needed in the classroom to help the educational efforts flow smoothly. And since teachers are human too, there were times I witnessed the children of MIA parents being treated differently than children whose parents were visible and supportive. No, they were not physically abused, but they just weren’t afforded as much patience, understanding or even sympathy as students whose parents took the time to come in, chat with teachers and offer support.

What was a typical day like in the classroom for you?

My day began around 6:20 a.m. when the special needs bus pulled onto the lot with the children. My class was a “system” class, meaning my students were from all over the system, not just within the neighborhood, so the buses had to leave early to pick everyone up.

Once in the classroom, we had only a few minutes for personal hygiene before breakfast was served. Since my students had severe academic and developmental delays, their social skills were pretty low. Our morning ritual was brushing teeth, combing hair, checking clothing, and so forth. Then we headed to the cafeteria for breakfast, cleaned up behind ourselves, and returned to the classroom. Sometimes, if the cafeteria was too noisy or one of my students was having an emotional morning, we brought our trays back to the classroom and ate there.

Next, we engaged in “post office” where students visited the wooden wall cubby, found their own names (letter and name recognition), retrieved papers or notes or graded homework, and left whatever they had brought for me. Next, we did what I call “warm-ups,” which is where students are given a quickie test that refreshes their memory about what they learned the day before. For example, in a math class, I would give each student a sheet of paper with whatever we had learned (i.e., 2 times tables, or 1-digit addition). I set an egg timer, then allowed four or five minutes to complete the paper. This exercise woke those little brains up and got them ready for a stimulating morning.

In reading, I alternated between allowing children to read aloud (or alone) and having them listen as I read. I had purchased a set of the literary classics, like “Black Beauty,” “Tom Sawyer,” and “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” and I would read a chapter while they listened, then ask questions. At the end of the book (usually ten chapters spread over ten days), we discussed what we remembered, then I rented the film from our library so that we could watch the movie and compare it to what we read in the book.

We ate lunch in a little section of the cafeteria that was allotted for our use, or we ate in our classroom, depending upon how keyed up the students were at the time.

We also had classes in survival skills (reading survival signs, learning to cross the street) and physical education. It should be noted that although most of my students were physically whole, their academic, social or developmental skills were so fractured that they could not function in a gymnasium filled with so-called “regular” students. We always had the gymnasium to ourselves, and we played group and individual games, as the situation called.

Though my goal was to guide my students toward independence, there was very little opportunity for independence. For example, I would have loved to be able to allow students who had been exceptionally well-behaved to go to the library alone (with the librarian’s permission, of course), but that could never happen. Some of my students were moderately disturbed, and were too impulsive to be left to themselves. A simple walk to the library alone could end in a fight or destruction of property. Those students who could be trusted alone were usually too low-functioning to use a catalog, find their own books, and sometimes, to even compose a sentence. This meant that I always had to be with them; they could not walk to the restroom alone, go to their lockers alone, or eat lunch without my watchful eye.

Amongst your students were some with profound hearing loss. How did you encourage classroom interaction and keep them engaged in the material?

Aside from physical accommodations (i.e., speaking more loudly, offering—not insisting—to allow them to sit in the front of the class, etc.), I used tried and true methods that had always worked with my type of classroom. I organized my classroom into smaller, two-person peer-tutoring groups. I paired the profoundly hard-of-hearing student with other students who complemented their skills. For example, I paired a regular-hearing student who was weak in math skills but strong in reading skills with a hard-of-hearing student who was strong in math and weak in reading. I paired the students who loved to talk with the profoundly hard-of-hearing because I knew they wouldn’t mind repeating themselves. I paired students who had the patience of Job with students who tried your patience on every hand.

But of special note, my peer-tutoring groups were never one-sided. No matter the child’s disability or academic weakness, he/she always had to eventually play “teacher” in the group. This means that instead of always being the one who sits there while the other student does all the talking, students rotate their roles, and the profoundly hard-of-hearing student eventually became the instructor.

In addition, I used the “seven ways of teaching” method in my classroom. Whatever our particular theme was for that grading period, I wrote my lessons toward the different intelligences, including kinesthetic (touch), interpersonal reinforcement (the peer tutoring model), logical (math), verbal expression and intrapersonal. Since we all learn in at least one of these ways, I was sure to include the method(s) that assisted the profoundly hard-of-hearing as well as the other students.

Do you have any particular views on classroom inclusion vs. pull-out therapy for special ed, or group therapy vs. one-on-one sessions? Does one or the other seem to work best for students with hearing loss?

I believe inclusion should be available for those who can handle it, or those who can work their way up from a restricted classroom like mine to the inclusion classroom, but I don’t believe it should be the only avenue. It’s not always the level of academic difficult that’s a challenge to “special” students. Sometimes it’s the environment. Take restaurants: Why do some customers fare well in crowded restaurants with loud music, wild bars or laid-back service, but other need soft music, soft lighting, and reserved behavior? Answer that question and you’ll understand why some children simply don’t fare well in regular classrooms. I don’t think one works any better than the other for children with hearing loss, I just think it’s up to the teacher to be sure the classroom “makes sense” for all the students.

Your research links low-income families with academic disadvantages, and you propose that baby sign language can help bridge that gap. Can you discuss the benefits of baby sign language for our readers?

Baby Sign educates parents (especially lower-income parents like single mothers and fathers) on ways to interact with and understand their children’s needs. This interaction demands that parent and child spend more time together, and this in turn encourages bonding and influences the child’s emotional, behavioral, social and educational well-being. In addition, this pre-verbal interaction boosts the child’s vocabulary, makes babies more alert to their surroundings and encourages their mothers/fathers to take an active role in their educational progress.

How would you go about teaching a baby his first sign?

Let’s assume a mother brings a baby to me that is a few months old. I would encourage that mother to begin signing to her baby right away, but I would also advise her that most babies won’t show any sign that they understand what you’re doing until around 6 months of age, and they won’t have enough dexterity to even try to sign back until around 8 or 9 months old.

I would teach the mom to begin with the most important signs: milk, pick me up, mommy, daddy, dog…that sort of thing. I would teach mom to always, always speak while signing. For instance, I would tell mom:

“If your baby is crying, say, ‘What’s the matter? Why are you crying?’ (make sign for crying); ‘Are you hungry? Do you want milk?’ (make the sign for milk).

I would advise mom to always speak and always sign; be consistent, and don’t give up, even when the baby looks at you like you’ve lost your mind, because one day, the baby will sign back. I’d also advise mom to watch the baby very carefully for reactions. For example, when the baby cries and mom asks if she wants milk, then makes the sign for milk, the baby may not be able to make the sign for the word “yes.” However, if the baby stops crying and begin smiling when mom makes the sign for milk, this may be proof that the baby is beginning to understand the connection between the word and the sign.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

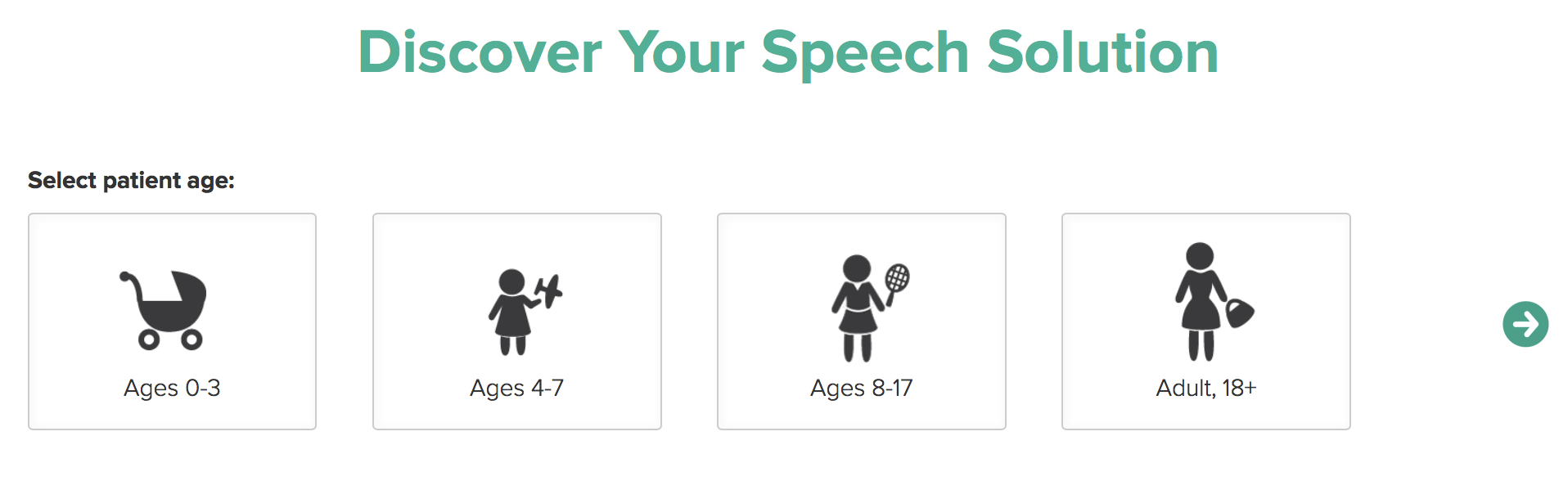

Indeed, repetition is so crucial for a child’s progress. Parental involvement in the classroom is also key. In addition to asking your child’s teacher and speech-language pathologist (SLP) about activities to work on at home with your child, you can also use the resources at Speech Buddies’ University for parents. And be sure to use the resources on Rita Lorraine Hubbard’s website for reading ideas for your child.

We greatly appreciate your taking the time to share your experiences and advice for parents, Rita!