An Interview with Lori Steed Sortino

This week, Lori Steed Sortino shares her experiences of raising her son, Daniel, who is Deaf. Lori’s blog, Deaf Son, Hearing Mother, emphasizes the positives. Daniel opened Lori’s eyes to a new world of possibilities. Despite the obstacles in his way, Daniel thrived and later became a successful college student. However, the journey wasn’t easy. Lori and her now ex-husband Joe fought to become advocates for their child and faced a great deal of resistance from the school district. While Daniel’s teachers wanted to help him, they were stuck in a system that was unresponsive to Daniel’s needs because of budget constraints. After her difficult experiences, Lori was inspired to work with a parent advocacy group to ensure that the needs of other Deaf children are being met. She emphasizes how critical it is for parents to join a network of support.

You’ve maintained the positive attitude that having a child who is Deaf is an opportunity to experience the world in different ways. Was there ever a time, perhaps when Daniel was first diagnosed, that you struggled to come to terms with it?

The thing I struggled with the most was dealing with what other people said, not the fact that Daniel had a hearing loss or that there was a lot of work to do in solving the puzzles related to helping Daniel get access to everyone around him so that he could participate in all the adventures awaiting him.

The day Daniel had his ABR (brain stem test), the ENT (Ear Nose Throat) Dr. who delivered the test results said “Your son has about a 90 decibel bilateral hearing loss… You should have some genetic testing done.” That was the first thing I struggled with. How do you respond to that? My son is Deaf and what’s important to you is that we don’t have any more Deaf children? That felt horrible and confusing.

That afternoon, I stopped by the church office for a reason I have long forgotten. The church secretary said the usual “Hi, how are you?” and I responded, breaking the news to someone for the first time, totally un-coached and unprepared, “Well, we just had Daniel’s hearing tested and he has a permanent severe hearing loss. I’m just still in shock.” She replied, “Shock?! You knew he wasn’t hearing things. How could it be a shock?” I was tender and in a very vulnerable place and this response jarred me.

So that was day one. After that I went home and my husband Joe and I just hibernated for about 24 hours to let things soak in and to process. This is one of those life reset buttons where you very suddenly feel this reality shift. It was extremely draining. By the next evening we were strategizing and into project management; beginning to take action on what we needed to do, which was get information. Once we had processed the event and started taking action, things moved forward.

Navigating the IFSP and IEP processes can be overwhelming. Were your experiences with early intervention and special education generally positive? Were Daniel’s schools receptive to his needs?

Getting Daniel through the system or working with school districts was not a positive experience. There were teachers, educators, and specialists who were wonderful, but our experiences, all the way through 6th grade were difficult and wrought with conflict. The IFSP and IEP process was not the issue. Those are very excellent tools. The challenges were in having to advocate for our son’s needs (that the teachers agreed with) when the district did not want to provide services because of how money is distributed. That’s an extremely simplified version of a much more complex whole picture. I recognized how horrible it was that people (district employees) were put in the position of compromising a child’s access to language because they were measured on their performance with a budget; therefore concerned about over-committing resources. I also realized that there must be hundreds of parents out there without the ability, interest, drive, or financial means to do the research and education we had done to know how to advocate for our son. Most parents simply accept the district’s suggestions and let things go much longer.

We were in due process and mediation when Daniel was in preschool, fighting over 3 sessions of speech therapy a week instead of 2. It was a ridiculous thing to argue over. What we ended up finally winning (the 3 sessions a week) rarely actually happened, between holidays, staff in service days, IEP meetings that the speech therapist was required to attend or an occasional sick day, we ended up with usually 2 sessions a week. Can you imagine if we had not even asked for 3? This is one example of things that were going on all the time. And over each little thing, we had to evaluate if it was worth our time to pursue a formal complaint with the district because they had failed to provide the services they had agreed to in the IEP.

Most of the time we worked to keep good relationships with all of the educators and specialists and we worked closely to maximize Daniel’s support without rocking the boat, because seriously, that is extremely stressful for everyone, not to mention expensive. We would look at Daniel’s progress and if we felt it was acceptable, we’d let the violations go. The violations were continuous and we had to be on top of the schools all the time.

The best thing we did for ourselves was continue to educate ourselves on the system, the state guidelines, and all of the laws that could be used to get Daniel the tools and resources he needed and to keep the district in check.

Besides the mediation in preschool, we also had to request an assessment through the state school for the Deaf when Daniel was in 1st grade because there was so much disagreement about his language needs and appropriate services. For Daniel’s kindergarten year, they had hired a high school graduate who had taken sign language in high school. She was a very sweet girl, but I was inviting her over and having her watch ASL tapes with me to try to get her skills up. She quit after the year was over, and then the next interpreter was better, but his language and communication skills were not keeping up with grade level. He had no language peers because he was going to our neighborhood school, so what he was missing was natural language development, and the school, district, and IEP team did not understand. They had never dealt with a child with severe hearing loss. The waiting list for the state school assessment was about a year, if my memory serves me.

Again, there were individual district employees who really wanted to help and were wonderful caring people, but they didn’t have the knowledge needed to be able to address Daniel’s issues. The state assessment was helpful and became a guide for the next several years’ IEPs. The next challenge was that even though the district now had this state level supported assessment and recommendations to follow, they had no idea how to go about carrying out the recommendations. “How do we provide him with language modeling? Why isn’t his interpreter enough?” I needed to help the district understand how to accomplish this and convince them why it had to be done, and soon. I felt very inadequate in even thinking about how I might convince the school district. I didn’t have statistics or experience. I had my knowing and intuition as a mother and as someone who had attended numerous conferences and trainings and lived with this little guy on a daily basis. I knew what he needed but I didn’t know how to put an argument together. I called on the Executive Director for a local agency who I had met and knew could explain this to them from a position of experience and authority. It worked. They listened to her and they got it.

Then we had to find a language model to hire. We searched and searched and the nearest one we could find who was willing to take the job was 90 miles away. He did it for a while but finally it just became too time-consuming for his schedule and the district (even with my help) could not locate another one.

We had issue after issue after issue. We tried the state school when he entered 6th grade, still trying to address his delay in social language and social skills, but that presented new and different issues, so we brought him back to a new local school district. Joe and I had divorced and Joe and his wife Bridgette were now living in a different county, which allowed Daniel to enroll in that district. There were at least a small group of DHH (deaf or hard of hearing) students at the schools he attended and we had wonderful support; the professionals knew what to do with Deaf students. Daniel began to excel, finally. That’s what it took.

Daniel worked with multiple speech therapists as a child. What types of techniques were helpful for him?

Games! Games were motivating and kept his interest. He also liked stickers and charts that showed his achievements. The hand positions and motions used with speech therapy to tell him tongue positions or combined sounds were helpful as he learned to read, as a way to communicate the various pronunciations of the same letter or letter combinations, such as the “ch” in cherry versus the “ch” in Cheri (his aunt’s name).

In addition to pronunciation, a profoundly Deaf individual needs whole language exposure. We labeled everything in the house: “door,” “refrigerator,” “chair,” “mirror.” We bought a Polaroid camera, and carried it with us to reinforce family members’ names, experiences, etc. with a photo and an immediate label on the lower white section. This was before the digital age!

To reinforce what he was working on at school, there was a notebook in his backpack that his speech therapist would write in so that we could work on the same things at home, and let her know how things went on our end.

You’re a consultant for the Deaf Education and Families Project (DEAF Project). Can you tell us a bit about your work with them?

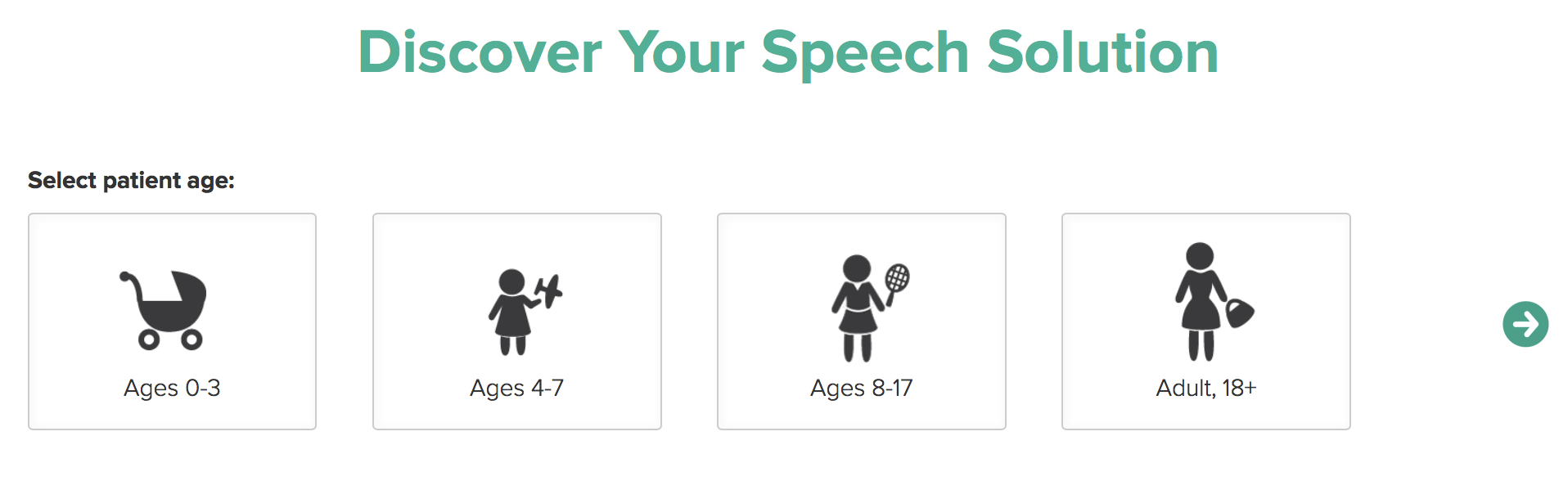

I do face-to-face and online trainings with parent mentors that are hired with grant funding to be available for parents whose children have had a hearing loss identified. The hearing coordination centers are encouraged to refer families to Parent Links, which serves families with children from birth to age 3. DEAF Project serves the families from age 3 on. What I do is work with the parent mentors and parent volunteers, provide an orientation to the program, remind them to use their gifts and strengths, develop their listening and modeling skills, and provide ongoing support as needed. I also help with their database and change management, which I have experience in.

As a consultant, my focus is on personal leadership, which is knowing who you are, understanding your gifts and strengths, and taking the personal responsibility (that’s the leadership piece) to manager your life and your career. When I was approached by the DEAF Project team, I was thrilled to be able to bring what I do into helping parents. DEAF Project and Parent Links, both, are programs that address the major unique needs of parents with Deaf or hard of hearing children.

The program provides parent mentors and key parent volunteers for families to talk to. The missing link when I found out my son was Deaf was knowing anyone to talk to about it who would understand what I was going through. There were no referral programs at that time, so my experience was isolation. This was also before the internet and Google searches or Facebook! Several months after Daniel was diagnosed we were able to find an adult education sign language class and the woman teaching the class was a sign language interpreter (who graduated from CSUN, by the way, where DEAF Project coordination now resides). She was able to give our phone number to the parents of other Deaf students in the school district so that we could connect to another parent.

I remember that first phone call with Norma Arthurs, who I still see and talk to occasionally. It was the beginning of the end of isolation as a parent. Norma also worked as an aid in Daniel’s preschool class for a couple of years. These kinds of connections are the foundation of support for parents. My experience at that point is why I believe so strongly in the program and value the work I do with them so much.

What advice would you give to other parents who are struggling with a diagnosis of hearing loss in a child?

Get in contact with a support network of other parents that have been through this and go to every training and conference you possibly can. Take extra special care of yourself because this will burn you out if you don’t and then you’re no good to anyone. I work training parents to become parent mentors and key parent volunteers to be there for you. Call the organization closest to you and get connected. Every parent I’ve trained, when I ask them why they want to be a parent mentor, answers with one of two things: “Because I don’t want another parent to have to go through what I went through,” or “I had a parent mentor and I can’t imagine what I would have done without her.” I want to be there in that way for other parents. It’s SO important.”

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Thanks so much, Lori, for sharing your family’s story and your excellent advice! Sometimes it’s difficult to go up against an administration, but parent advocacy groups like Lori’s are there to help. Be sure to check out Lori’s blog at Deaf Son, Hearing Mother.